Mesh Generation with Python

Do you ever find yourself needing a simple mesh for testing purposes, but you don’t want to harass your art team for the billionth time? Python is beautiful language for generating 3D mesh data. In this entry, I’ll show how to use the pyeuclid module (available on google code) combined with OpenCTM (available on sourceforge). I’ll explore various ways to generate mathematical shapes, including rule-based generation similar to Structure Synth.

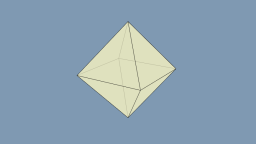

Simple Example: Octohedron

At a minimum, meshes are usually represented by two lists: a list of vertex positions (XYZ data) and a list of vertex indices (the three corners of each triangle). In Python, these are naturally represented with lists of 3-tuples. So, building an octohedron shape is easy:

from math import *

def octohedron():

"""Construct an eight-sided polyhedron"""

f = sqrt(2.0) / 2.0

verts = [ \

( 0, -1, 0),

(-f, 0, f),

( f, 0, f),

( f, 0, -f),

(-f, 0, -f),

( 0, 1, 0) ]

faces = [ \

(0, 2, 1),

(0, 3, 2),

(0, 4, 3),

(0, 1, 4),

(5, 1, 2),

(5, 2, 3),

(5, 3, 4),

(5, 4, 1) ]

The tricky part is packaging up these lists into a format that OpenCTM can understand. To pull this off, we’ll need to crack our knuckles with the ctypes module. The key OpenCTM function for writing out a mesh is ctmDefineMesh, and its Python binding looks like this:

ctmDefineMesh = _lib.ctmDefineMesh

ctmDefineMesh.argtypes = [CTMcontext,

POINTER(CTMfloat), CTMuint, # Pointer to vertex data & vertex count

POINTER(CTMuint), CTMuint, # Pointer to index data & triangle count

POINTER(CTMfloat)] # Optional pointer to surface normals

OpenCTM can represent far more than just positions and normals, but this is an easy place to get started.

So, we need to convert our Python list-of-tuples into ctypes pointers. Here’s a generic function that does just that, allowing you to pass in a custom type for the T argument (e.g., c_float):

from ctypes import *

def make_blob(verts, T):

"""Convert a list of tuples of numbers into a ctypes pointer-to-array"""

size = len(verts) * len(verts[0])

Blob = T * size

floats = [c for v in verts for c in v]

blob = Blob(*floats)

return cast(blob, POINTER(T))

Let’s place the above code snippet into a file called blob.py and the octohedron function into a file called polyhedra.py. It’s now fairly simple to generate the mesh file:

from ctypes import * from openctm import * import polyhedra, blob verts, faces = polyhedra.octohedron() pVerts = blob.make_blob(verts, c_float) pFaces = blob.make_blob(faces, c_uint) pNormals = POINTER(c_float)() ctm = ctmNewContext(CTM_EXPORT) ctmDefineMesh(ctm, pVerts, len(verts), pFaces, len(faces), pNormals) ctmSave(ctm, "octohedron.ctm") ctmFreeContext(ctm)

That’s all you need to generate a simple mesh file! Note that the OpenCTM package comes with a viewer application and a conversion tool, just in case you need some other format.

Polyhedra Subdivision

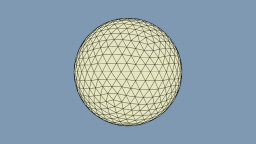

Generating a sphere is typically done by evaluating a parametric function, but if you want to avoid pole artifacts, subdividing an icosahedron produces nice results. (We’ll cover parametric functions later in the article.) Here’s a simple subdivision algorithm that uses pyeuclid for vector math. The subdivide function takes a pair of lists (verts & faces, as usual) and performs in-place subdivision, returning the modified pair of lists:

from euclid import *

def subdivide(verts, faces):

"""Subdivide each triangle into four triangles, pushing verts to the unit sphere"""

triangles = len(faces)

for faceIndex in xrange(triangles):

# Create three new verts at the midpoints of each edge:

face = faces[faceIndex]

a,b,c = (Vector3(*verts[vertIndex]) for vertIndex in face)

verts.append((a + b).normalized()[:])

verts.append((b + c).normalized()[:])

verts.append((a + c).normalized()[:])

# Split the current triangle into four smaller triangles:

i = len(verts) - 3

j, k = i+1, i+2

faces.append((i, j, k))

faces.append((face[0], i, k))

faces.append((i, face[1], j))

faces[faceIndex] = (k, j, face[2])

return verts, faces

It’s now very easy to generate a nice sphere, subdividing as many times as needed, depending on the desired level of detail:

num_subdivisions = 3

verts, faces = polyhedra.icosahedron()

for x in xrange(num_subdivisions):

verts, faces = polyhedra.subdivide(verts, faces)

pVerts = blob.make_blob(verts, c_float)

pFaces = blob.make_blob(faces, c_uint)

# etc...

I recommend using an icosahedron as the starting point, rather than an octohedron or tetrahedron. It produces a more pleasing, symmetric geodesic pattern.

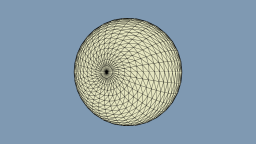

Parametric Surfaces

As promised, here’s how to generate parametric surfaces, following our existing list-of-tuples convention. The generation function takes three arguments: the level-of-detail for the U coordinate, the level-of-detail for the V coordinate, and a function object that converts the domain coordinate into a range coordinate.

from math import *

def surface(slices, stacks, func):

verts = []

for i in xrange(slices + 1):

theta = i * pi / slices

for j in xrange(stacks):

phi = j * 2.0 * pi / stacks

p = func(theta, phi)

verts.append(p)

faces = []

v = 0

for i in xrange(slices):

for j in xrange(stacks):

next = (j + 1) % stacks

faces.append((v + j, v + next, v + j + stacks))

faces.append((v + next, v + next + stacks, v + j + stacks))

v = v + stacks

return verts, faces

To use the above function, we need to pass in a function object. Of course, this can be a sphere:

def sphere(u, v):

x = sin(u) * cos(v)

y = cos(u)

z = -sin(u) * sin(v)

return x, y, z

Assuming the above two snippets are in a file called parametric.py, here’s how our top-level generation script looks:

slices, stacks = 32, 32 verts, faces = parametric.surface(slices, stacks, parametric.sphere) pVerts = blob.make_blob(verts, c_float) pFaces = blob.make_blob(faces, c_uint) # etc...

A huge number of shapes can be generated by providing alternative parametric functions. Here’s a personal favorite of mine, the Klein bottle:

def klein(u, v):

u = u * 2

if u < pi:

x = 3 * cos(u) * (1 + sin(u)) + (2 * (1 - cos(u) / 2)) * cos(u) * cos(v)

z = -8 * sin(u) - 2 * (1 - cos(u) / 2) * sin(u) * cos(v)

else:

x = 3 * cos(u) * (1 + sin(u)) + (2 * (1 - cos(u) / 2)) * cos(v + pi)

z = -8 * sin(u)

y = -2 * (1 - cos(u) / 2) * sin(v)

return x, y, z

Another type of parametric surface is a general tube shape, which brings us to the next section.

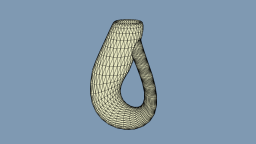

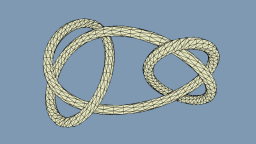

Tube Tessellation

Sometimes, all you have on hand is a simple path in 3-space; you’ve got a twisty-turny, infinitely thin length of hair, and you want to build a tube around it. The path might be supplied by an artist, or it might be generated by a mathematical function.

In another words, you’ve got list of center points for a hypothetical tube. The math for tessellating a tube is not complex, but it helps if you have the pyeuclid module at your disposal. All you need is a bit of linear algebra magic for performing a change-of-basis transformation on a plain ol’ 2D circle. Here’s a parametric function that takes a domain coordinate, a function object for the path in 3-space, and a radius:

def tube(u, v, func, radius):

# Compute three basis vectors:

p1 = Vector3(*func(u))

p2 = Vector3(*func(u + 0.01))

A = (p2 - p1).normalized()

B = perp(A)

C = A.cross(B).normalized()

# Rotate the Z-plane circle appropriately:

m = Matrix4.new_rotate_triple_axis(B, C, A)

spoke_vector = m * Vector3(cos(2*v), sin(2*v), 0)

# Add the spoke vector to the center to obtain the rim position:

center = p1 + radius * spoke_vector

return center[:]

One gotcha is the perp function, which is not part of the pyeuclid module. Every vector in 3-space has an infinite number of perpendicular vectors, so here we simply choose a random one:

def perp(u):

"""Randomly pick a reasonable perpendicular vector"""

u_prime = u.cross(Vector3(1, 0, 0))

if u_prime.magnitude_squared() < 0.01:

u_prime = u.cross(v = Vector3(0, 1, 0))

return u_prime.normalized()

Generic tube tessellation is useful for visualizing various knot shapes. Here’s the formula for the so-called “Granny Knot” (depicted above):

def granny_path(t):

t = 2 * t

x = -0.22 * cos(t) - 1.28 * sin(t) - 0.44 * cos(3 * t) - 0.78 * sin(3 * t)

y = -0.1 * cos(2 * t) - 0.27 * sin(2 * t) + 0.38 * cos(4 * t) + 0.46 * sin(4 * t)

z = 0.7 * cos(3 * t) - 0.4 * sin(3 * t)

return x, y, z

To tessellate the actual tube, we need to use this function in conjunction with our existing parametric surface function. Here’s how our top-level script can do so:

def granny(u, v):

return tube(u, v, granny_path, radius = 0.1)

verts, faces = parametric.surface(slices, stacks, granny)

pVerts = make_blob(verts, c_float)

pFaces = make_blob(faces, c_uint)

# etc...

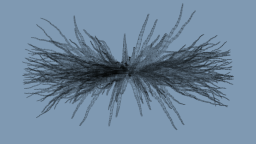

Rule-Based Generation

Rule-based generation is a cool way of generating fractal-like shapes. StructureSynth and Context Free are a couple popular packages for generating these type of meshes, but it’s actually pretty easy to write an evaluator from scratch. In this section, we’ll devise a simple XML-based format for representing the rules, and we’ll use Python to evaluate the rules and dump out a mesh.

The XML file defines a set of rules, each of which contains a list of instructions. There are only two instructions: the instance instruction, which stamps down a small predefined shape, and the call function, which calls another rule. Multiple rules can have the same name, in which case the evaluator picks a rule at random. Rules can be assigned a weight if you want to give them a higher probability of being chosen. If you don’t specify a weight, it defaults to one.

Each instruction has an associated count and an associated set of transformations. If you don’t specify a count, it defaults to 1. If you don’t specify a transformation, it defaults to an identity transformation.

Since recursion is a fundamental aspect of rule-based mesh generation, our evaluator requires you to specify a maximum call depth using the max_depth attribute in the top-level XML element.

Now, without further ado, here’s the XML description for the preceding tree shape, which is based on a Structure Synth example:

<rules max_depth="200">

<rule name="entry">

<call transforms="ry 180" rule="spiral"/>

</rule>

<rule name="spiral" weight="100">

<instance shape="tubey"/>

<call transforms="ty 0.4 rx 1 sa 0.995" rule="spiral"/>

</rule>

<rule name="spiral" weight="100">

<instance shape="tubey"/>

<call transforms="ty 0.4 rx 1 ry 1 sa 0.995" rule="spiral"/>

</rule>

<rule name="spiral" weight="100">

<instance shape="tubey"/>

<call transforms="ty 0.4 rx 1 rz -1 sa 0.995" rule="spiral"/>

</rule>

<rule name="spiral" weight="6">

<call transforms="rx 15" rule="spiral"/>

<call transforms="ry 180" rule="spiral"/>

</rule>

</rules>

Every description must contain at least one rule named entry; this is the starting point for the evaluator. Note the mini-language used for specifying transformations. It’s a simple string consisting of translations, rotations, and scaling operations. For example, tx n means “translate n units along the x-axis”, ry theta means “rotate theta degrees about the y-axis”, and sa f means “scale all axes by a factor of f“.

It’s surprisingly easy to write a Python module that slurps up the preceding XML, evaluates the rules, and dumps out a mesh file. The module has only one public function: the surface function, which takes an XML string for input and returns lists of vertex positions and indices:

from math import *

from euclid import *

from lxml import etree

from lxml import objectify

import random

def surface(rules_string):

verts, faces = [], []

tree = objectify.fromstring(rules_string)

max_depth = int(tree.get('max_depth'))

entry = pick_rule(tree, "entry")

process_rule(entry, tree, max_depth, verts, faces)

print "nverts, nfaces = ", len(verts), len(faces)

return verts, faces

The module defines three private functions:

- pick_rule

-

Takes the entire DOM and a string name for input; chooses a random rule with the given name, respecting the weights. Returns the XML element for the chosen rule.

- parse_transform

-

Parses a transformation string and returns the resulting matrix.

- process_rule

-

The key function in the evaluator. Takes an XML element for a specific rule to evaluate and a transformation matrix. Contains a loop to respect the count attribute, and calls itself as needed.

To see the source code for these functions, check out the downloads section.

Before finishing up the blog entry, let me leave you with another cool rule-based shape inspired by a Structure Synth example:

The XML for this is pretty simple:

<rules max_depth="20">

<rule name="entry">

<call count="300" transforms="ry 3.6" rule="arm"/>

</rule>

<rule name="arm">

<call transforms="sa 0.9 rz 6 tx 1" rule="arm"/>

<instance transforms="s 1 0.2 0.5" shape="box"/>

</rule>

<rule name="arm">

<call transforms="sa 0.9 rz -6 tx 1" rule="arm"/>

<instance transforms="s 1 0.2 0.5" shape="box"/>

</rule>

</rules>

Downloads

If you want, you can download all the python scripts necessary for generating these meshes as a zip file. I consider this code to be on the public domain, so don’t worry about licensing.

You’ll need to download the OpenCTM SDK and the pyeuclid module from their respective sources.