Archive for the ‘raycasting’ tag

Single-Pass Raycasting

Raycasting over a volume requires start and stop points for your rays. The traditional method for computing these intervals is to draw a cube (with perspective) into two surfaces: one surface has front faces, the other has back faces. By using a fragment shader that writes object-space XYZ into the RGB channels, you get intervals. Your final pass is the actual raycast.

In the original incarnation of this post, I proposed making it into a single pass process by dilating a back-facing triangle from the cube and performing perspective-correct interpolation math in the fragment shader. Simon Green pointed out that this was a bit silly, since I can simply do a ray-cube intersection. So I rewrote this post, showing how to correlate a field-of-view angle (typically used to generate an OpenGL projection matrix) and focal length (typically used to determine ray direction). This might be useful to you if you need to integrate a raycast volume into an existing 3D scene that uses traditional rendering.

To have something interesting to render in the demo code (download is at the end of the post), I generated a pyroclastic cloud as described in this amazing PDF on volumetric methods from the 2010 SIGGRAPH course. Miles Macklin has a simply great blog entry about it here.

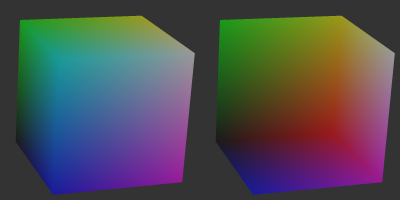

Recap of Two-Pass Raycasting

Here’s a depiction of the usual offscreen surfaces for ray intervals:

Front faces give you the start points and the back faces give you the end points. The usual procedure goes like this:

-

Draw a cube’s front faces into surface A and back faces into surface B. This determines ray intervals.

- Attach two textures to the current FBO to render to both surfaces simultaneously.

- Use a fragment shader that writes out normalized object-space coordinates to the RGB channels.

-

Draw a full-screen quad to perform the raycast.

- Bind three textures: the two interval surfaces, and the 3D texture you’re raycasting against.

- Sample the two interval surfaces to obtain ray start and stop points. If they’re equal, issue a discard.

Making it Single-Pass

To make this a one-pass process and remove two texture lookups from the fragment shader, we can use a procedure like this:

-

Draw a cube’s front-faces to perform the raycast.

- On the CPU, compute the eye position in object space and send it down as a uniform.

- Also on the CPU, compute a focal length based on the field-of-view that you’re using to generate your scene’s projection matrix.

- At the top of the fragment shader, perform a ray-cube intersection.

Raycasting on front-faces instead of a full-screen quad allows you to avoid the need to test for intersection failure. Traditional raycasting shaders issue a discard if there’s no intersection with the view volume, but since we’re guaranteed to hit the viewing volume, so there’s no need.

Without further ado, here’s my fragment shader using modern GLSL syntax:

out vec4 FragColor;

uniform mat4 Modelview;

uniform float FocalLength;

uniform vec2 WindowSize;

uniform vec3 RayOrigin;

struct Ray {

vec3 Origin;

vec3 Dir;

};

struct AABB {

vec3 Min;

vec3 Max;

};

bool IntersectBox(Ray r, AABB aabb, out float t0, out float t1)

{

vec3 invR = 1.0 / r.Dir;

vec3 tbot = invR * (aabb.Min-r.Origin);

vec3 ttop = invR * (aabb.Max-r.Origin);

vec3 tmin = min(ttop, tbot);

vec3 tmax = max(ttop, tbot);

vec2 t = max(tmin.xx, tmin.yz);

t0 = max(t.x, t.y);

t = min(tmax.xx, tmax.yz);

t1 = min(t.x, t.y);

return t0 <= t1;

}

void main()

{

vec3 rayDirection;

rayDirection.xy = 2.0 * gl_FragCoord.xy / WindowSize - 1.0;

rayDirection.z = -FocalLength;

rayDirection = (vec4(rayDirection, 0) * Modelview).xyz;

Ray eye = Ray( RayOrigin, normalize(rayDirection) );

AABB aabb = AABB(vec3(-1.0), vec3(+1.0));

float tnear, tfar;

IntersectBox(eye, aabb, tnear, tfar);

if (tnear < 0.0) tnear = 0.0;

vec3 rayStart = eye.Origin + eye.Dir * tnear;

vec3 rayStop = eye.Origin + eye.Dir * tfar;

// Transform from object space to texture coordinate space:

rayStart = 0.5 * (rayStart + 1.0);

rayStop = 0.5 * (rayStop + 1.0);

// Perform the ray marching:

vec3 pos = rayStart;

vec3 step = normalize(rayStop-rayStart) * stepSize;

float travel = distance(rayStop, rayStart);

for (int i=0; i < MaxSamples && travel > 0.0; ++i, pos += step, travel -= stepSize) {

// ...lighting and absorption stuff here...

}

The shader works by using gl_FragCoord and a given FocalLength value to generate a ray direction. Just like a traditional CPU-based raytracer, the appropriate analogy is to imagine holding a square piece of chicken wire in front of you, tracing rays from your eyes through the holes in the mesh.

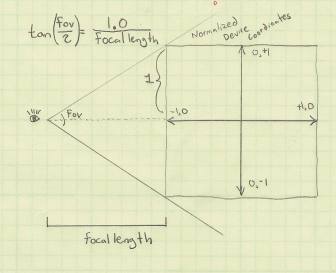

If you’re integrating the raycast volume into an existing scene, computing FocalLength and RayOrigin can be a little tricky, but it shouldn’t be too difficult. Here’s a little sketch I made:

In days of yore, most OpenGL programmers would use the gluPerspective function to compute a projection matrix, although nowadays you’re probably using whatever vector math library you happen to be using. My personal favorite is the simple C++ vector library from Sony that’s included in Bullet. Anyway, you’re probably calling a function that takes a field-of-view angle as an argument:

Matrix4 Perspective(float fovy, float aspectRatio, float nearPlane, float farPlane);

Based on the above diagram, converting the fov value into a focal length is easy:

float focalLength = 1.0f / tan(FieldOfView / 2);

You’re also probably calling function kinda like gluLookAt to compute your view matrix:

Matrix4 LookAt(Point3 eyePosition, Point3 targetPosition, Vector3 up);

To compute a ray origin, transform the eye position from world space into object space, relative to the viewing cube.

Downloads

I’ve tested the code with Visual Studio 2010. It uses CMake for the build system.

I consider this code to be on the public domain. Enjoy!