Path Instancing

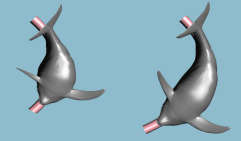

Instancing and skinning are like peas and carrots. But remember, skinning isn’t the only way to deform a mesh on the GPU. In some situations, (for example, rendering aquatic life), a bone system can be overkill. If you’ve got a predefined curve in 3-space, it’s easy to write a vertex shader that performs path-based deformation.

Path-based deformation is obviously more limited than true skinning, but gives you the same performance benefits (namely, your mesh lives in an immutable VBO in graphics memory), and it is simpler to set up; no fuss over bone matrices.

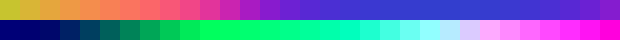

Ideally your curve has two sets of data points: a set of node centers and a set of orientation vectors. Your first thought might be to store them in an array of shader uniforms, but don’t forget that modern vertex shaders can make texture lookups. It just so happens that these two sets of data can be nicely represented by a pair of rows in an RGB floating-point texture, like so:

Here’s the beauty part: by creating your texture with a GL_LINEAR filter, you’ll be able to leverage dedicated interpolation hardware to obtain points (and orientation vectors) that live between the node centers. (Component-wise lerping of orientation vectors isn’t quite mathematically kosher, but who’s watching?)

But wait, there’s more! Even the wrap modes of your texture will come in handy. If your 3-space curve is a closed loop, you can use GL_REPEAT for your S coordinate, and voilà — your shader need not worry its little head about cylindrical wrapping!

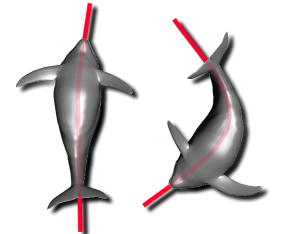

One gotcha with paths is that you’ll want to enforce an even spacing between nodes; this helps keep your shader simple. If your shader assumes a uniform distribution of path nodes, your models can become alarmingly foreshortened. For example, here’s a dolphin that’s tied to an elliptical path, before and after node re-distribution:

Now, without further ado, here’s my vertex shader. Note the complete lack of trig functions; I can’t tell you how many times I’ve seen graphics code that makes costly sine and cosine calls when simple linear algebra will suffice. I’m using old-school GLSL (e.g., attribute instead of in) to make my demo more amenable to Mac OS X.

attribute vec3 Position;

uniform mat4 ModelviewProjection;

uniform sampler2D Sampler;

uniform float TextureHeight;

uniform float InverseWidth;

uniform float InverseHeight;

uniform float PathOffset;

uniform float PathScale;

uniform int InstanceOffset;

void main()

{

float id = gl_InstanceID + InstanceOffset;

float xstep = InverseWidth;

float ystep = InverseHeight;

float xoffset = 0.5 * xstep;

float yoffset = 0.5 * ystep;

// Look up the current and previous centerline positions:

vec2 texCoord;

texCoord.x = PathScale * Position.x + PathOffset + xoffset;

texCoord.y = 2.0 * id / TextureHeight + yoffset;

vec3 currentCenter = texture2D(Sampler, texCoord).rgb;

vec3 previousCenter = texture2D(Sampler, texCoord - vec2(xstep, 0)).rgb;

// Next, compute the path direction vector. Note that this

// can be optimized by removing the normalize, if you know the node spacing.

vec3 pathDirection = normalize(currentCenter - previousCenter);

// Look up the current orientation vector:

texCoord.x = PathOffset + xoffset;

texCoord.y = texCoord.y + ystep;

vec3 pathNormal = texture2D(Sampler, texCoord).rgb;

// Form the change-of-basis matrix:

vec3 a = pathDirection;

vec3 b = pathNormal;

vec3 c = cross(a, b);

mat3 basis = mat3(a, b, c);

// Transform the positions:

vec3 spoke = vec3(0, Position.yz);

vec3 position = currentCenter + basis * spoke;

gl_Position = ModelviewProjection * vec4(position, 1);

}

The shader assumes that the undeformed mesh sits at the origin, with its spine aligned to the X axis. The way it works is this: first, compute the three basis vectors for a new coordinate system defined by the path segment. Next, place the basis vectors into a 3×3 matrix. Finally, apply the 3×3 matrix to the spoke vector, which goes from the mesh’s spine out to the current mesh vertex. Easy!

By the way, don’t feel ashamed if you’ve never made an instanced draw call with OpenGL before. It’s a relatively new feature that was added to the core in OpenGL 3.1. Before that, it was known as GL_ARB_draw_instanced. At the time of this writing, it’s still not supported on Mac OS X. Here’s how you do it with an indexed array:

glDrawElementsInstanced(GL_TRIANGLES, faceCount*3, GL_UNSIGNED_INT, 0, instanceCount);

When making this call, OpenGL automatically sets up the gl_InstanceID variable, which can be accessed from your vertex shader. Simple!

Downloads

The demo code uses a subset of the Pez ecosystem, which is included in the zip below. It uses a cool python-based build system called WAF. I tested it in a MinGW environment on a Windows 7 machine.

I consider this code to be on the public domain. Here’s a little video of the demo: